Toilet or lavatory? How words Britons use betray national obsession with class

January 7, 2016 10.59am GMT

Simon Horobin

Professor of English Language and Literature, University of Oxford

Dinner is not served. Luncheon, on the other hand…

Few things are as British as the notion of class – and little betrays it as effectively as how you speak and the words you use.

Usefully for those keen to decode this national peculiarity, 2016 is the 60th anniversary of the publication of Noblesse Oblige, a slim collection of essays edited by the notorious author and socialite Nancy Mitford, which investigated the characteristics of the English aristocracy.

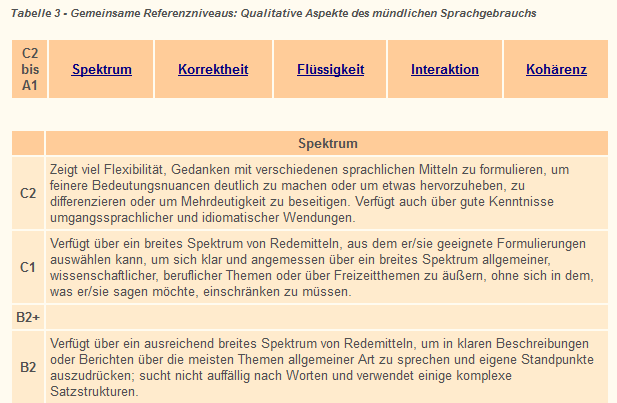

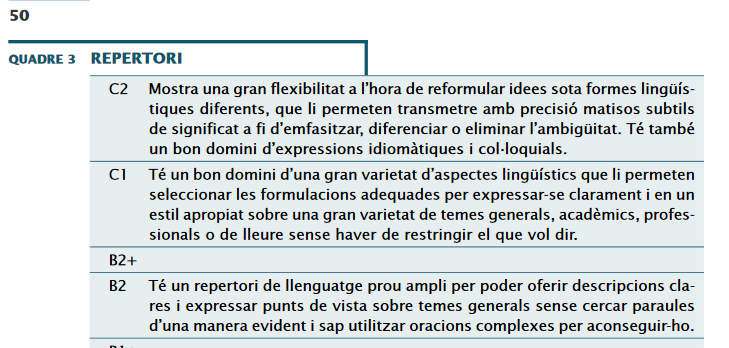

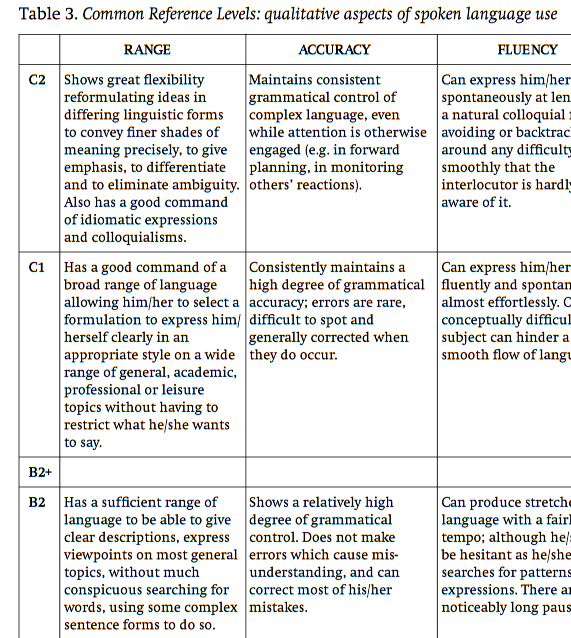

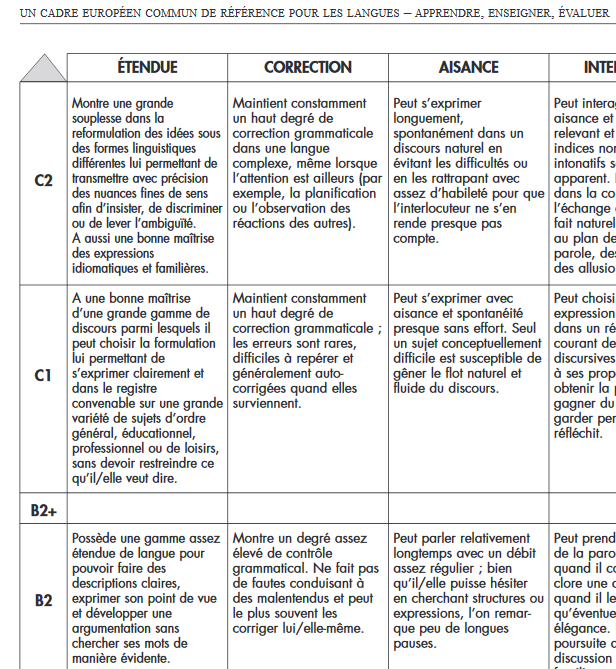

The volume opened with An Essay in Sociological Linguistics by Alan Ross, a professor of Linguistics at Birmingham University, in which he set out the differences between “U” (Upper-class) and “non-U” (Middle Class) usages, covering forms of address, pronunciation and the use of particular words.

It was the last of these categories – how to refer to the midday meal, the lavatory, the living room – that captured the interest of the class-conscious of 1950s England. Indeed, if the use of dinner (U form luncheon), toilet (U form lavatory), lounge (U form drawing room) and other non-U markers were not so explicitly marked before the publication of Noblesse Oblige, they certainly became so after it. Despite the Oxford English Dictionary attesting to the use of serviette in English from the 15th century, a headnote to the dictionary entry warns that it has “latterly come to be considered vulgar”.

Fish-knives? How vulgar!

Given his academic credentials, you might assume that Ross’s essay drew upon extensive scientific research. But in fact his claims were based on personal observation and anecdote. When he did draw upon textual sources, these are literary fiction of earlier generations such as the works of Jane Austen. The only contemporary source he cites is – somewhat circularly – Mitford’s own novel The Pursuit of Love (1945).

But while Ross invented the terms U and non-U, the idea that the words we use betray our social origins can be traced back to the early 20th century. In her essay on “Social Solecisms” (1907), Lady Agnes Grove lamented the middle-class use of words such as reception, couch, serviette (instead of the “honest napkin”), and expressions including going up to town (meaning London) and inviting people for the weekend.

Napkin or serviette? Be careful how you answer.

For Lady Grove, the use of such words was the unrefined linguistic equivalent of employing napkin-rings and fish-knives – and putting milk into the tea-cup before pouring the tea. The middle-class fondness for fish-knives and milk-in-first were mercilessly satirised by John Betjeman in his contribution to Noblesse Oblige: How to Get on in Society, with its memorable opening line: “Phone for the fish-knives, Norman”.

Perhaps most influential, however, was the discussion of “Genteelisms” included by H.W. Fowler in his Modern English Usage (1926) – the 20th century’s bible for linguistic purists. Fowler defined “genteelism” as the substitution for the natural term of a synonym that is “thought to be less soiled by the lips of the common herd, less familiar, less plebeian, less vulgar, less improper, less apt to come unhandsomely betwixt the wind & our nobility”. For Fowler, the genteel offer ale rather than beer; invite one to step (not come) this way; and assist (never help) one another to potatoes.

The seven deadly sins

Even though they are now effectively a century old and based on little more than upper-class snobbishness combined with Mitford’s teasing sense of humour, U and non-U distinctions continue to be cited as contemporary class markers. Kate Fox’s bestselling study of English behaviour, Watching the English (2004), warns her readers against the “Seven Deadly Sins” which will immediately reveal you as a member of the middle class, or resident of “Pardonia”: pardon, toilet, serviette, dinner (to refer to the midday meal), settee, lounge, sweet (instead of pudding).

Despite living in a more egalitarian and less class-conscious society, we continue to find a fascination with such linguistic dividers. When Prince William and Kate Middleton split up in 2007 the press blamed it on Kate’s mother’s linguistic gaffes at Buckingham Palace, where she reputedly responded to the Queen’s How do you do? with the decidedly non-U Pleased to meet you (the correct response being How do you do?), and proceeded to ask to use the toilet (instead of the U lavatory).

In his contribution to Noblesse Oblige, Evelyn Waugh observed that while most people have fixed ideas about proper usage, which they use to identify those who are NLO (“not like one”), these are often based on little more than personal prejudices and an innate sense of one’s own superiority. The cartoonist Osbert Lancaster, who supplied drawings for Noblesse Oblige, satirised this view through his creation Lady Littlehampton, who confidently pronounced: “If it’s Me, it’s U”.

Meanwhile, in America

How far do such categories resonate with speakers of English throughout the world? Attempts to identify US equivalents have suggested parallel distinctions between the U words mother, gal, fellow, thanks much and the non-U mom, woman, guy, thanks very much. While toilet is an acceptable way to refer to the object itself, delicate euphemisms such as restroom or bathroom are preferred ways of describing the room in which it is found.

What’s U today?

What are the linguistic markers that Britons use today to identify those who are non-U, MIF “milk-in-first” and – that most heinous of all crimes – NLO?

At the beginning of 2016, U terms such as looking-glasses, drawing rooms, scent and wirelesses are quaint archaisms and the province of period drama – think of the Dowager Countess’s disdain for the word weekend in the ITV drama Downton Abbey.

A recent article by Flora Watkins in The Lady magazine titled “Pardon: that’s practically a swear-word” extends the list of non-U terms with others to be avoided if you want to mix with the right sort in Britain today: cleaner (U daily), posh (U smart), nana (U granny), expecting (U pregnant) and passed (U dead). While expecting and passed capture the U preference for straight talking over the non-U genteel tendency towards euphemism, others seem more debatable.

Having guests to your house (not home or property) for dinner, supper or an evening meal (never high tea) remains a minefield of linguistic etiquette: do you serve them pudding, sweet, dessert or afters; show them to the lounge, sitting room, front room or living room; offer them a seat on the settee, sofa, or couch, direct them to the toilet, lavatory, loo or WC?

Such apparently innocent choices are still likely to prompt people to make judgements about your class, though it’s likely that the rules will just keep on changing. Sorry – or should I say, “pardon”? – the class conscious will just have to keep up.